Bloomberg Businessweek

This Economist Foresees 15 Years of Labor Shortages

By Peter Coy

March 21, 2014

Economists who worry about high unemployment are a dime a dozen, or 0.83¢

each, as they will point out. Itfs less common to find an economist predicting

an era of chronic labor shortages, with employers struggling to fill

openings. One who does see things that way is Gad Levanon, the Israeli-born director

of macroeconomic research at the Conference Board, a business research group

founded in 1916.

I sat down with Levanon this week to ask him to explain why hefs swimming

against the tide on the topic of labor. Herefs what he said:

Bureau of Labor Statistics

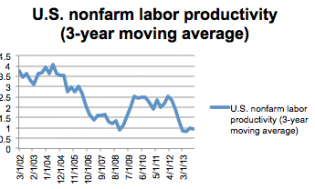

Productivity: If itfs true that

companies are automating and streamlining jobs out of existence, we should see a

big jump in the governmentfs measure of output per hour worked—i.e.,

productivity. We see no such thing. In fact, when averaged over a three-year

period, productivity has been drifting lower. This key fact simply doesnft fit

the conventional wisdom of a hyperefficient economy pushing workers into the

street.

Bureau of Labor Statistics

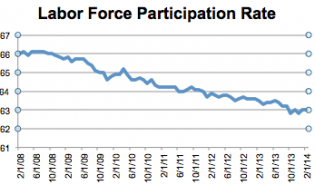

Baby-Boom Retirements: Lots of things about the future are

unknown, but one thing we can say with certainty is that in 25 years, baby

boomers will be 25 years older than they are today.

The aging of the

workforce has pushed down the share of Americans who are in the labor force,

either working or looking for work. The labor force participation rate will

continue to fall in coming years as the vast majority of those who havenft

already retired do so in the next couple of decades. Companies will struggle to

replace those retirees, Levanon predicts.

Bureau of Labor Statistics

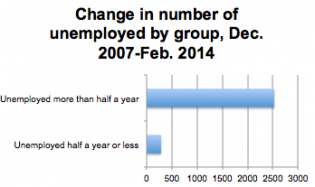

Two-Tier Market: Itfs quite possible for labor market

shortages to co-exist with high unemployment for those people who lack the

skills that employers are seeking, Levanon says. In fact, thatfs whatfs

happening. For people who have been out of work for less than half a year, the

job market is pretty much back to normal, while therefs still an enormous bulge

in the number of people who have been out of work for more than half a year, as

this chart shows.

And these numbers donft

even reflect those who have dropped out of the labor force altogether. The

upshot is that the labor market could start to get tight—and wages could start

to rise—even at low levels of employment, Levanon says.

History: Automation has been a fact of life in the working

world for generations, and never before has it generated mass unemployment,

Levanon says. True, it dislodges people from old jobs and forces them to find

new niches, but itfs never caused permanently high joblessness, he says, asking:

gSo why should it be different now?h

The Conference Board economistfs message rings true to many people in the

business world, who have long been complaining that itfs a sellerfs market for

labor despite the above-average unemployment rate—6.7 percent in February.

gTherefs a greater demand for workers than there is a supply with the right

skill sets,h George Prest, chief executive officer of the Material Handing

Institute of America, told me yesterday. gIf we could somehow magically have

people go to one of these [training] programs, theyfd have a job very

quickly.h

Levanon says both Republicans and Democrats have a political incentive to

exaggerate the slackness of demand for labor—Republicans because perceived

weakness makes the Obama administration look like a poor steward of the economy,

and Democrats because it justifies more stimulus. So does that put Levanon on

the side of those who think the Federal Reserve should start raising interest

rates sooner?

Actually, no. He thinks a tighter labor market would help lift some people

out of long-term unemployment, because employers couldnft afford to be so picky.

And he doesnft think therefs a grave risk of an inflationary wage-price spiral.

On the whole, Levanon thinks the big labor issue facing the U.S. economy over

the next 15 years will be shortages, not surpluses.

Coy is

Bloomberg Businessweek's economics editor. His Twitter handle is

@petercoy.